Golden-winged warbler

| Golden-winged warbler | |

|---|---|

| |

| Female golden-winged warbler | |

| |

| Male golden-winged warbler | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Parulidae |

| Genus: | Vermivora |

| Species: | V. chrysoptera

|

| Binomial name | |

| Vermivora chrysoptera (Linnaeus, 1766)

| |

| |

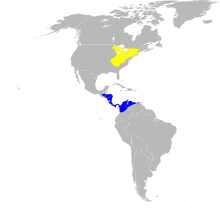

| Range of V. chrysoptera (note: missing distribution in the Caribbean) Breeding range Wintering range

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The golden-winged warbler (Vermivora chrysoptera) is a New World warbler. It breeds in southeastern and south-central Canada and in the Appalachian Mountains in northeastern to north-central United States. The majority (~70%) of the global population breeds in Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Manitoba. Golden-winged warbler populations are slowly expanding northwards, but are generally declining across its range, most likely as a result of habitat loss and competition/interbreeding with the very closely related blue-winged warbler, Vermivora cyanoptera. Populations are now restricted to two regions: the Great Lakes and the Appalachian Mountains. The Appalachian population has declined 98% since the 1960s and is significantly imperiled.[2] The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has been petitioned to list the species under the Endangered Species Act of 1973 and is currently reviewing all information after issuing a positive finding.[3] Upon review, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service found that the petition to list the species as endangered or threatened presents "substantial scientific or commercial information indicating that listing the golden-winged warbler may be warranted."[4]

Etymology

[edit]The genus name Vermivora is from Latin vermis "worm", and vorare, "to devour", and the specific chrysoptera is from Ancient Greek khrusos, "gold", and pteron, "wing".[5]

Description

[edit]This is a small warbler, measuring 11.6 cm (4.6 in) long, weighing 8–10 g (0.28–0.35 oz), and having a wingspan range 20 cm.[6] The male has black throat, black ear patch bordered in white, and a yellow crown and wing patch. Females appear similar to males, with a light gray throat and light gray ear patches. In both sexes, extensive white on the tail is conspicuous from below. Underparts are grayish white and the bill is long and slender. Juvenile individuals appear similar to females, regardless of sex.[7]

-

Male

-

Male

-

Male

-

Front Male

-

Female

Life history

[edit]Golden-winged warblers are migratory, breeding in eastern North America and wintering in southern Central America and the neighboring regions in Colombia, Venezuela, and Ecuador. They are very rare vagrants elsewhere.

Golden-winged warblers breed in open scrubby areas, wetlands, and mature forest adjacent to those habitats. Incubation of eggs, from laying to hatch, lasts 11–12 days.[8] They lay 3–6 eggs (often 5) in a concealed cup nest on the ground or low in a bush.

Nestling golden-winged warblers feed almost entirely on caterpillars (especially leafrollers) delivered by their parents.[9] Adult diets are less thoroughly described, but it is assumed they subsist heavily on caterpillars, and occasionally spiders.[10] They have strong gaping (opening) musculature around their bill, allowing them to uncover hidden caterpillars.[11]

Their song is variable, but is most often perceived as a trilled bzzzzzzz buzz buzz buzz. The call is a buzzy chip or zip.

Male Golden-winged warblers use their brilliant yellow crowns, black throats, and white tail feather patches to signal habitat quality. Birds with more ornate ornaments protect higher quality territories and are typically less aggressive than their less brilliantly-colored conspecifics. However, ornamentation has not been shown to be linked with overall reproductive success. This is likely because golden-winged warblers with less ornamentation likely compensate for this with increased aggression.[12]

Five geotracked golden-winged warblers in Tennessee were observed migrating hundreds of miles south, presumably avoiding tornadic storms, in April 2014. Individuals left prior to the arrival of the storm, perhaps after detecting it due to infrasound.[13]

Habitat Selection

[edit]Golden-winged warblers are neotropical-nearctic migrants, and their habitat selectivity varies seasonally. Golden-winged warblers wintering in Costa Rica select premontane evergreen forest rather than tropical dry forest plant communities. Golden-winged warblers forage in hanging dead leaves, which are often a result of intermediate disturbances to the forest plant community.[14]

During the breeding season, golden-winged warblers nest in shrubland and regenerating forest communities created and maintained by disturbance. This dependency on early-successional plant communities is part of the reason golden-winged warbler populations are declining.[15]

Hybridization

[edit]This species forms two distinctive hybrids with blue-winged warblers where their ranges overlap in the Great Lakes and New England area. The more common, genetically dominant Brewster's warbler is gray above and whitish (male) or yellow (female) below. It has a black eyestripe and two white wingbars.

The rarer recessive Lawrence's warbler has a male plumage with green and yellow above and yellow below, with white wing bars and the same face pattern as male golden-winged. The female is gray above and whitish below with two yellow wing bars and the same face pattern as female golden-winged.

An exceptionally rare triple-hybrid, the Burket's warbler, was described in Pennsylvania in 2018 by researchers at Cornell University's Lab of Ornithology.[16][17] The Burket's warbler was determined through genetic testing to be the offspring of a Brewster's warbler and another closely related species, the chestnut-sided warbler.[16] Brewster's and Lawrence's warblers can vary considerably in their physical features and sing songs of either blue-winged or golden-winged warblers. The colour of the throat patch reliably correlates with hybrid type, but colour of the underparts is highly variable between different hybrids.[18] The only known Burket's warbler sang a chestnut-sided warbler's song.[19]

Genetic introgression occurs across their range, producing cryptic hybrids (morphologically pure individuals with small amounts of blue-winged warbler DNA). These hybrids may be present in low numbers even on the edges of golden-winged warbler range, far from any populations of blue-winged warblers.

Hybridization between golden-winged warblers and blue-winged warblers is likely occurring at a much higher rate than initially thought. Genetic analysis has allowed scientists to more accurately quantify extra-pair copulation, and one study showed EPC was occurring in 55% of golden-winged warbler nests, resulting in phenotypic golden-winged warblers that were actually hybrids.[20]

Interspecific interactions

[edit]In 2015, scientists observed a strange event. A female golden-winged warbler abandoned her two fledgling chicks 5 and 9 days after fledging. The two chicks were subsequently "adopted" by a male black-and-white warbler, which fed the fledglings for 23 days until they reached independence.[21]

Golden-winged warbler nests are frequently parasitized by brown-headed cowbirds; up to 30% of golden-winged warbler nests may be parasitized in habitats they share with cowbirds.[22]

References

[edit]- ^ BirdLife International (2018). "Vermivora chrysoptera". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22721618A132145282. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22721618A132145282.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ "Golden-winged Warbler: Conservation Strategy and Resources". Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology. 2019-05-07. Retrieved 2022-09-19.

- ^ "Golden-winged Warbler". Max Patch, NC. Retrieved 2022-09-19.

- ^ "90-Day Finding on a Petition To List the Golden-Winged Warbler as Endangered or Threatened | U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service". FWS.gov. 2 June 2011. Retrieved 2022-09-19.

- ^ Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London, United Kingdom: Christopher Helm. pp. 105, 400. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ Oiseaux.net. "Paruline à ailes dorées - Vermivora chrysoptera - Golden-winged Warbler". www.oiseaux.net. Retrieved 2020-09-30.

- ^ "Vermivora chrysoptera". Michigan Natural Features Inventory. Michigan State University Extension. 2023. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ Will, T. C. 1986. The behavioral ecology of species replacement: Blue-winged and Golden-winged warblers in Michigan. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

- ^ Streby, Henry A.; Peterson, Sean M.; Lehman, Justin A.; Kramer, Gunnar R.; Vernasco, Ben J.; Andersen, David E. (2014). "Do digestive contents confound body mass as a measure of relative condition in nestling songbirds?". Wildlife Society Bulletin. 38 (2): 305–310. doi:10.1002/wsb.406.

- ^ Bellush, E. C., J. Duchamp, J. L. Confer, and J. L. Larkin. 2016. Influence of plant species composition on Golden-winged Warbler foraging ecology in north-central Pennsylvania. Pp. 95–108 in H. M. Streby, D. E. Andersen, and D. A. Buehler (editors). Golden-winged Warbler ecology, conservation, and habitat management. Studies in Avian Biology (no. 49), CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- ^ Ficken, Millicent S.; Ficken, Robert W. (1968). "Ecology of blue-winged warblers, golden-winged warblers and some other Vermivora". The American Midland Naturalist. 79 (2): 311–319. doi:10.2307/2423180.

- ^ Jones, John Anthony; Tisdale, Anna C.; Bakermans, Marja H.; Larkin, Jeffery L.; Smalling, Curtis G.; Siefferman, Lynn (2017). "Multiple Plumage Ornaments as Signals of Intrasexual Communication in Golden-Winged Warblers". Ethology. 123 (2): 145–156. Bibcode:2017Ethol.123..145J. doi:10.1111/eth.12581. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ Henry M. Streby et al. (2015) "Tornadic Storm Avoidance Behavior in Breeding Songbirds"Current Biology, 25(1), pp. 98 – 102.

- ^ Chandler, Richard (2011). "Habitat quality and habitat selection of golden-winged warblers in Costa Rica: an application of hierarchical models for open populations". Journal of Applied Ecology. 48 (4): 1038–1047. Bibcode:2011JApEc..48.1038C. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2664.2011.02001.x.

- ^ Leuenberger, Wendy; McNeil, Darin J.; Cohen, Jonathan; Larkin, Jeffery L. (2017). "Characteristics of Golden-winged Warbler territories in plant communities associated with regenerating forest and abandoned agricultural fields". Journal of Field Ornithology. 88 (2): 169–183. doi:10.1111/jofo.12196. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ a b Toews, David P. L.; Streby, Henry M.; Burket, Lowell; Taylor, Scott A. (2018-11-01). "A wood-warbler produced through both interspecific and intergeneric hybridization". Biology Letters. 14 (11): 20180557. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2018.0557. ISSN 1744-9561. PMC 6283930. PMID 30404868.

- ^ "'Newbie' bird watcher discovers extremely rare 3-species hybrid warbler | CBC Radio". CBC. Retrieved 2018-11-13.

- ^ Baiz, Marcella D; Kramer, Gunnar R; Streby, Henry M; Taylor, Scott A; Lovette, Irby J; Toews, David P L (2020-07-24). "Genomic and plumage variation in Vermivora hybrids". The Auk. 137 (3): ukaa027. doi:10.1093/auk/ukaa027. ISSN 1938-4254.

- ^ Daley, Jason (12 November 2018). "This Rare Warbler Is Three Species in One". Smithsonian Magazine.

- ^ Vallender, Rachel; Friesen, Vicki L.; Robertson, Raleigh J. (2007). "Paternity and performance of golden-winged warblers (Vermivora chrysoptera) and golden-winged X blue-winged warbler (V. pinus) hybrids at the leading edge of a hybrid zone". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 61 (12): 1797–1807. doi:10.1007/s00265-007-0413-3. S2CID 24177787. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ Fiss, Cameron J.; McNeil, Darin J.; Poole, Renae E.; Rogers, Karli M.; Larkin, Jeffery L. (2016). "Prolonged Interspecific Care of Two Sibling Golden-winged Warblers (Vermivora chrysoptera) by a Black-and-white Warbler (Mniotilta varia)". The Wilson Journal of Ornithology. 128 (4): 921–926. doi:10.1676/15-180.1. ISSN 1559-4491. S2CID 90636981.

- ^ Confer, John L.; Larkin, Jeffery L.; Allen, Paul E. (2003). "Effects of vegetation, interspecific competition, and brood parasitism on golden-winged warbler (Vermivora chrystoptera) nesting success". The Auk. 120 (1): 138–144. doi:10.1093/auk/120.1.138.

External links

[edit]- Golden-winged warbler - Vermivora chrysoptera - USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Golden-winged warbler species account - Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- "Golden-winged warbler media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Golden-winged warbler photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)